Deep double descent explained (4/4)

Recent works analyzing over-parameterized regimes.

Optimization in the over-parameterized regime

For reasons that are still active research, overparameterization seems beneficial not only in the statistical learning framework, but from an optimization standpoint as well as it facilitates convergence to global minima, in particular with the gradient descent procedures.

The optimization problem can be framed as minimizing a certain loss function \(\LL(w)\) with respect to its parameters \(w \in \mathbb{R}^N\), such as the square loss \(\LL(w) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i, w) - y_i)^2\) where \(\{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^{n}\) is our given training dataset and \(f : (\mathbb{R}^d \times \mathbb{R}^N) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is our model.

Exercise 2. Assume that \(\ell: \mathcal{Y} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is convex and \(f : \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}\) is linear. Show that \(\ell \circ f\) is convex.

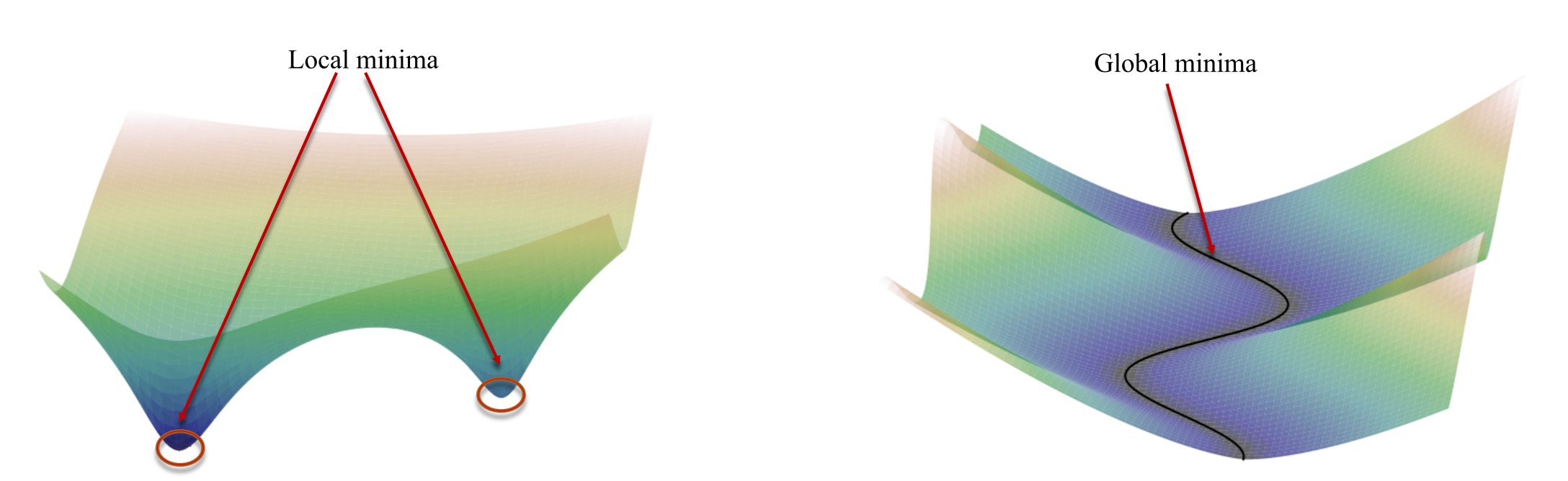

When \(f\) is non-linear however (which is habitually the case in deep learning) the landscape of the loss function is generally non-convex. Therefore, first order methods such as GD or SGD are likely to converge and get trapped in spurious local minima, depending on the initialization. Yet, in the over-parameterized regime where there are multiple global minima interpolating almost perfectly the data, it seems that SGD has no problem converging to these solutions, despite the highly non-convex setting. Recent works are trying to explain this phenomenon.

For instance, Oymak & Soltanolkotabi (2020)

In Liu et al. (2020)

Left : Loss landscape of under-parameterized models, locally convex

at local minima. Right : Loss landscape of over-parameterized models,

incompatible with local convexity. Taken from

Liu et al. (2020)

In addition to better convergence guarantees, over-parameterization can

even accelerate optimization. By working with linear neural networks

(hence fixed expressiveness), Arora et al. (2018)

Neural networks as a physical system : the jamming transition

In order to study the loss landscape, Spigler et al. (2019)

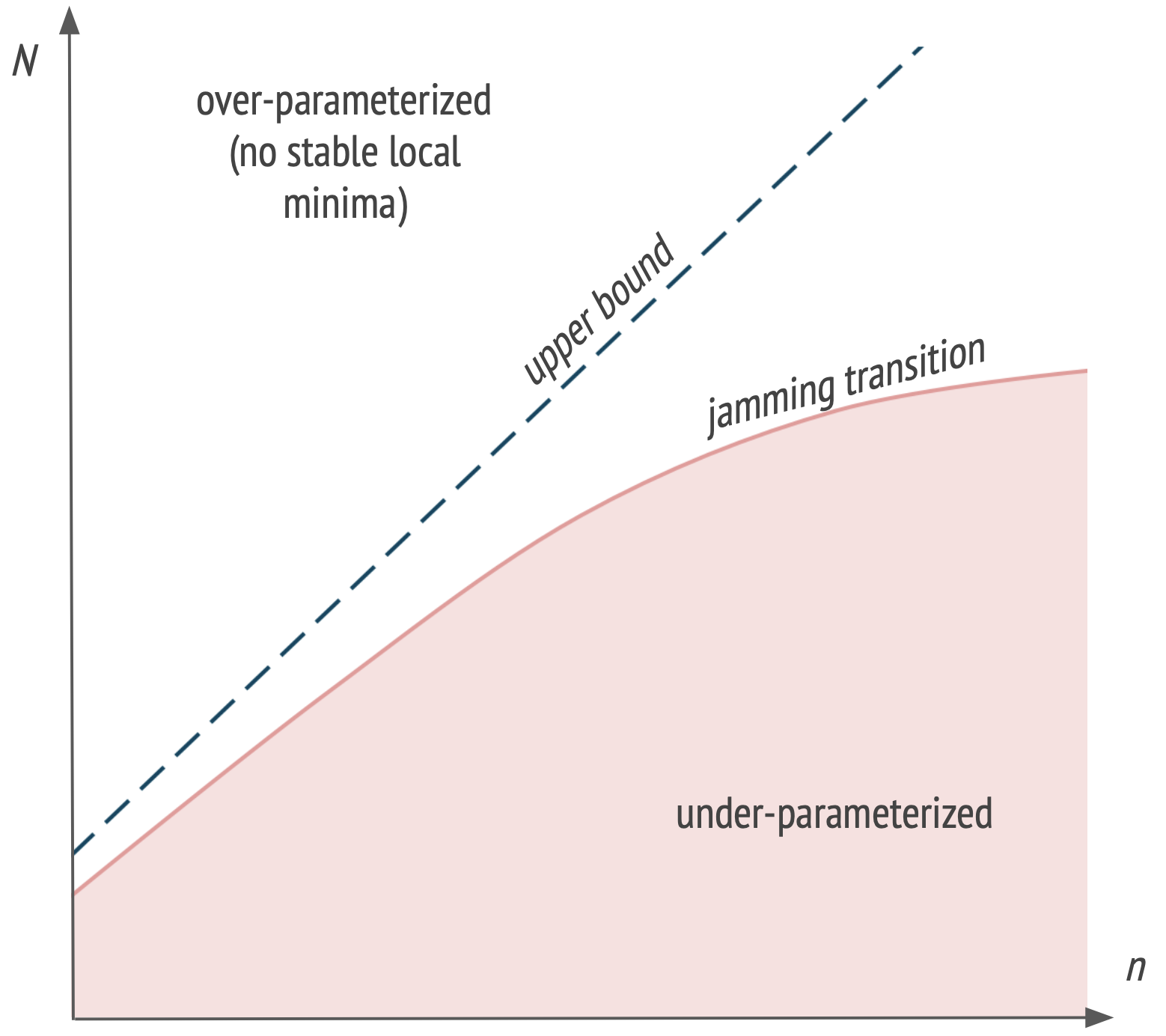

Using this analogy, they show that the behavior of deep networks near the interpolation point is similar to the behavior of some granular systems, that undergo a critical jamming transition when their density increases such that they are forced to be in contact one another. In the under-parameterized regime, not all the training examples can be classified correctly, which leads to unsatisfied constraints. But in the over-parameterized regime, there is no stable local minima : the network reaches a global minima zero training loss.

As illustrated in figure below, the authors are able to quantify the location of the jamming transition in the \((n, N)\) plane (considering \(N\) as the effective number of parameters of the network). Considering a fully-connected network with arbitrary depth, ReLU activation functions, and a dataset of size \(n\), they give a linear upper bound on the critical number of parameters \(N^*\) characterizing the jamming transition : \(N^* \leq \frac{1}{C_0} n\) where \(C_0\) is a constant. In their experiments, it seems that the bound is tight for random data but that \(N^*\) increases sub-linearly with \(n\) for structured data (e.g. MNIST).

\(N\) : degrees of freedom, \(n\) : training examples. Inspired from

Spigler et al.

Similarly to other works, they observe a peak in test error at the

jamming transition. In Geiger et al. (2020)

Conclusion

From a statistical learning point of view, deep learning is a

challenging setting to study, and some recent empirical successes are not

yet well understood. The double descent phenomenon, arising from

well-chosen inductive biases in the over-parameterized regime, has been

studied in linear settings

In addition to the references presented in this post, other lines of work seem promising.

Notably,